Envisioning an Intentional Socio-ecological Community, Part 2

Intentional Communities –Types and Roles

Recap

Part 1 in this series of exploring intentional communities addressed “why” concerns, with an overview of the socioecological challenges facing humanity and the planet. We learned that the primary motivation for humans to explore intentional communities is a response to concerns about the ongoing deteriorating conditions of society and the bio-ecosphere.

To reiterate a recurring theme, our self-perpetuating human predicament may be considered a metacrisis, a crisis-of-crises comprised of systemic social and ecological tipping points. A tipping point in any system—social or ecological—may be thought of as what happens when a system encounters changes, either a series of small changes or a sudden catastrophic incident (like an impact from space) that causes a bio-ecological system (biodiversity, ocean currents, climate, et al) to change from a state of equilibrium to one of collapsing.

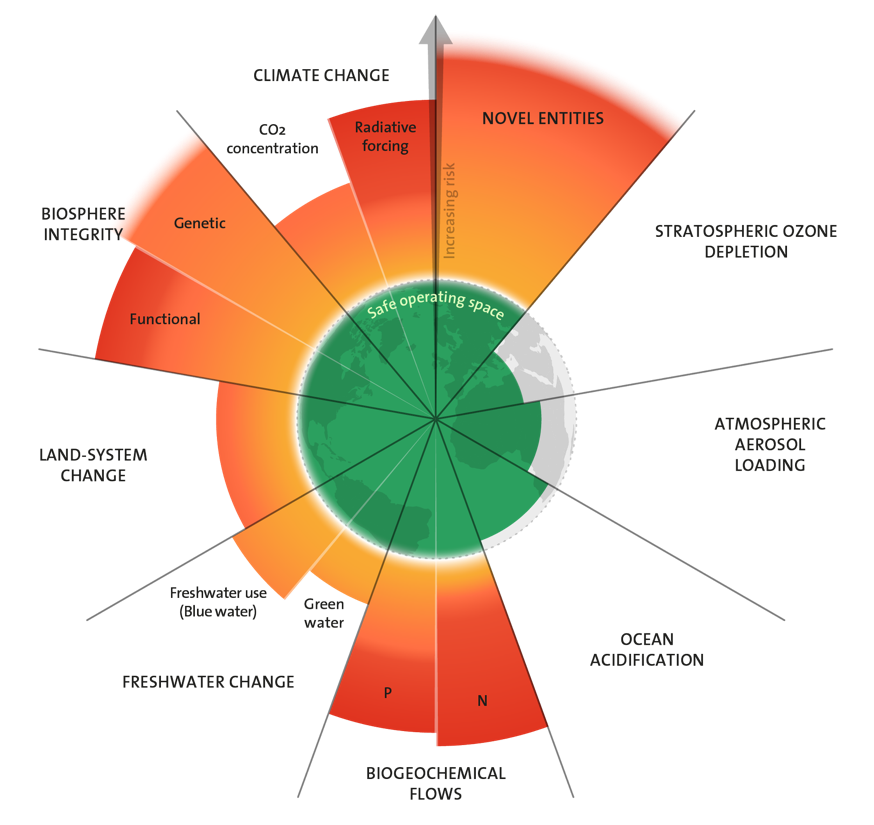

Climate change, which is intertwined with all other systems, may be considered the most comprehensive systemic crisis. As discussed in Part 1, the average global temperature is projected to attain a 2C (3.6F) rise in temperature above pre-industrial levels between 2034 and 2052. Unexpected sudden changes in systems overwhelmed with accumulating stresses may result in more crossover tipping points, in addition to the three already crossed: ocean acidification, atmospheric aerosol loading, and stratospheric ozone depletion.

The Stockholm Resilience Centre’s planetary boundaries framework highlights the rising risks from human pressure on nine critical global processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth. The following illustration (2023) shows the planetary boundaries, including the degree to which each is threatened or endangered. The green area represents the planet’s “safe operating space”.

Considerations for intentional-community living

Although this question was partially addressed in Part 1, it’s the speed at which planetary systems are weakening that motivates concerned individuals to consider all possible preparatory options. One sensible option for anyone concerned is to seek a living situation that evidences potential for providing a sustainable future. Deeply-concerned young adults are strongly advised to seek some form of intentional community (IC), a safe and caring environment that aims to create a resilient and sustainable way of life.

Of course, there are many types of intentional communities, including single-family units, from small modern families to large traditional families. People who have extended family members living in close proximity and maintaining close connections, can cultivate practices that encourage the sharing of certain possessions, services, interests, and activities. For aging folks, like me, selected senior-living complexes might provide safe havens.

In thinking about this topic, I realized that the social fraternity I joined in undergraduate college was an intentional community (IC), with designated “brothers” sharing values, principles, structured activities and responsibilities, a sense of belonging, and an established structure and governance. We also shared living facilities (a fraternity house), celebrated achievements and occasions, cooperated and collaborated on special projects, and played a significant role within a liberal-arts college’s academic, extra-curricular, and social life.

As for my interest in addressing this topic, it’s like this: If I were younger (say early 50s), I’d likely be deeply involved in exploring, and possibly helping organize a cooperative intentional community (IC). I’ve been mulling over this topic for a few years, and I continue modifying my concepts. But, so far, I envision living with a group of variably-aged and healthy like-minded people, mostly young adults. Long term, I would anticipate attaining a stable, sustainable community of approximately 100-150 people. Why this number?

According to British anthropologist Robin Dunbar, the size of a group should be based on the ability to function effectively in fulfilling intended purposes and goals, which is more likely to happen when all participants are known and trustworthy. This suggests that a start-up community might function well as a smaller group of around 15-30 well-known persons or fewer, as determined by participants’ qualifications and acceptance of carefully conceived, pre-established membership guidelines, which will be covered in subsequent posts.

It seems relevant to point out that the tribal sizes of paleolithic hunter-gatherers ranged from 20-60 members living in non-hierarchical, egalitarian bands and groups. This number also applies to early Paleo-Indians in the Americas prior to some settling down to practice simple farming and herding. In some cases, tribes gradually developed into small villages, followed by Mound Builder societies, nations, and urban centers (like Cahokia). Inevitably, for various reasons large populations collapsed, possibly due to wars, overpopulation, and diminishing food resources.

The above paragraph points out that, when any group grows too large, several conditions may be responsible, largely the result of increasing complexity in all aspects of living, including population expansion, diminishing resources, and social disintegration. Such outcomes help explain why maintaining a stable group size can help promote stability, resilience, and sustainability.

General criteria for evaluating potential intentional communities

I think any intentional community will have a better chance of surviving and succeeding when all participants adopt a similarly-conceived worldview, a belief system founded on a set of values, principles, concepts, objectives, and practices.

In a 2022 essay, Dr. Ted Trainer, founder of “Simpler Way, suggested that achieving a sustainable and just community requires addressing five strategies:

· simpler lifestyles, with greatly reduced material production and consumption;

· small, highly-efficient local economies with minimal dependence on globalism;

· more cooperative and participatory behaviors that enable personal development;

· a no-growth, profitless and market-driven economy focused on material sufficiency and satisfactory lifestyles; and

· values of frugality, self-sufficiency, giving and sharing, cooperation and collaboration, and rejection of acquisitiveness and competition.

The rationale for considering an intentional community concept may be understood by studying religious communities that have survived and flourished over decades, some for centuries. Christian-oriented communities like the Amish, Mennonites, Catholic Religious Communities, and Homestead Heritage provide success stories. Other effective ICs include Monasteries and Ashrams, religious communities with shared living spaces and routines. Hence, there’s ample proof that long-term success of such religious communities is largely attributed to their sharing a tradition founded on a set of beliefs, values, and behavioral guidelines.

Other types of ICs worth exploring are listed on this Wikipedia IC link, among them the six IC forms listed below:

· Communes: Groups living together, and often sharing resources and responsibilities, sometimes with a specific religious or spiritual focus.

· Ecovillages: Communities focused on creating resilience, sustainability, ecological living, and community building.

· Cohousing: Groups of families or individuals who share common facilities and living spaces, while also maintaining their own homes.

· Student Co-ops: Residential communities for students, often with a focus on affordability and community.

· Farming collectives: Communities that work together on a farm, often with a focus on organic or sustainable agriculture.

• Kibbutz: An Israeli collective community characterized by communal ownership of property and resources, cooperative living based on social equality and mutual aid, and self-supported by agricultural and/or industrial production.

Another factor to consider in evaluating any intentional community (IC) is where the greater community is located. For example, a co-housing community located in a large city will function differently than a farming cooperative in a rural area. In all cases, the surrounding socio-ecological environment will determine how the IC functions in meeting the needs of its members.

Such a community way of living may be considered as communitarianism, based on a political philosophy and social ideology that emphasizes the importance of community and social bonds in creating a thriving society founded on shared values, beliefs, and behaviors. Collectivism, a contrasting IC arrangement, generally prioritizing the collective’s needs and goals over individual interests. It seems that any form of IC should encourage the expansion of individual freedom in pursuing special interests that also serve to enhance community life.

Of course, when undertaking such a challenging project, it’s wise to proceed thoughtfully and cautiously, all the while adhering to predetermined first-things-first guidelines, which typically involves a step-by-step process in a succession of complex developmental stages. The standard procedure in forming any group is to begin with determining the group’s primary purpose, mission, or goal.

First things first – determining values, purpose, and goals

Either in evaluating existing ICs or forming a new one, it requires choosing to live with others according to shared life-affirming values and a common purpose, which involves cooperatively creating a desired lifestyle supported by a strong social network and a shared culture. For our purposes, a primary focus is to develop a resilient, sustainable way of living together.

For me, this would require all members observing the transcendental values of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty as guideposts in creating an existence that is meaningful and fulfilling—for all lifeforms. In addition, the universally accepted Golden Rule (to treat others as you wish to be treated) provides a universal guideline for creating moral and ethical behavior in all human (and non-human) relationships.

It's important to emphasize here that all bio-ecological lifeforms are essential parts of any community, which includes animals, insects, and plants, plus all societal infrastructures, geographical features, and essential life-supporting systems, especially healthy water, air, and soil. We humans must learn to think of ourselves as fully emmeshed beings in Nature, as a single mammal among all existing species. The failure to realize, acknowledge, and honor this reality has proven to be the root cause of our existential metacrisis.

Hence, it seems obvious that any successful IC will need to function harmoniously in cooperation with other groups and beings in advancing the common good. We are one, a part of the whole and interconnected and unified in the fabric of life. As the renowned biologist E. O. Wilson once wrote:

Only in the last moment of human history has the delusion arisen that people can flourish apart from the rest of the living world.

Finally, the ultimate goal or mission of a socio-ecologically oriented IC is mainly to create a harmonious, thriving, safe, resilient, and long-term sustainable community, inclusive of all lifeforms, natural materials, and the basic life-supporting resources of clean air, water, and soil. Given the deteriorating trajectory of humanity and the planet, what goal could be more important?

Wrap up

The section above presents a brief sketch of key values, beliefs, and guidelines that will be fleshed out further in the next two posts. In the meantime, I hope you will carefully digest all that’s been covered thus far. If exploring IC living is a strong interest, it will help to note your thoughts, concerns, and ideas in writing.

To help you get started, consider these questions: What kind of IC seems appealing, practical, and possible to you? What qualities and characteristics would you like community members to exhibit? What special knowledge and skills might you offer an IC community? Where would you like to live that might remain inhabitable long term, a geographical region where ample life-supporting materials and conditions will likely be available? Would you be sufficiently prepared and willing to live more simply, with reduced access to modern technologies, goods, and services? Is your current lifestyle sufficiently healthy in providing a moderate degree of physical work, like gardening? What other relevant questions or concerns do you have?

Until next time . . .

Clif